Stan Kenton Research Center

Stan Kenton Conducts

The Jazz Compositions of Dee Barton

LABEL Capitol

NO. 2932

FORMAT 12" Record

PRODUCER Lee Gillette

LINER NOTES Noel Wedder

PHOTOS Ed Simpson

LOCATION Capitol Tower Studios, Hollywood

RECORDING DATES 19-20 December 1967

Tracks

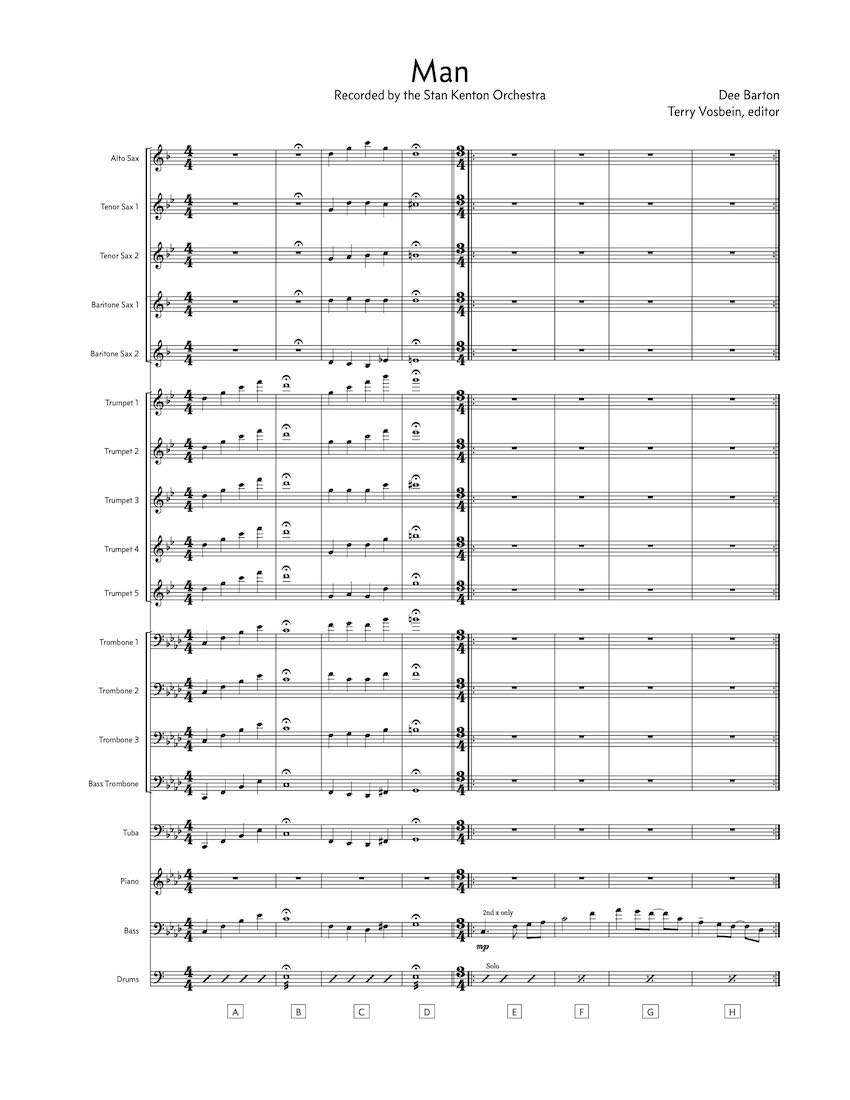

Man

Lonely Boy

The Singing Oyster

Dilemma

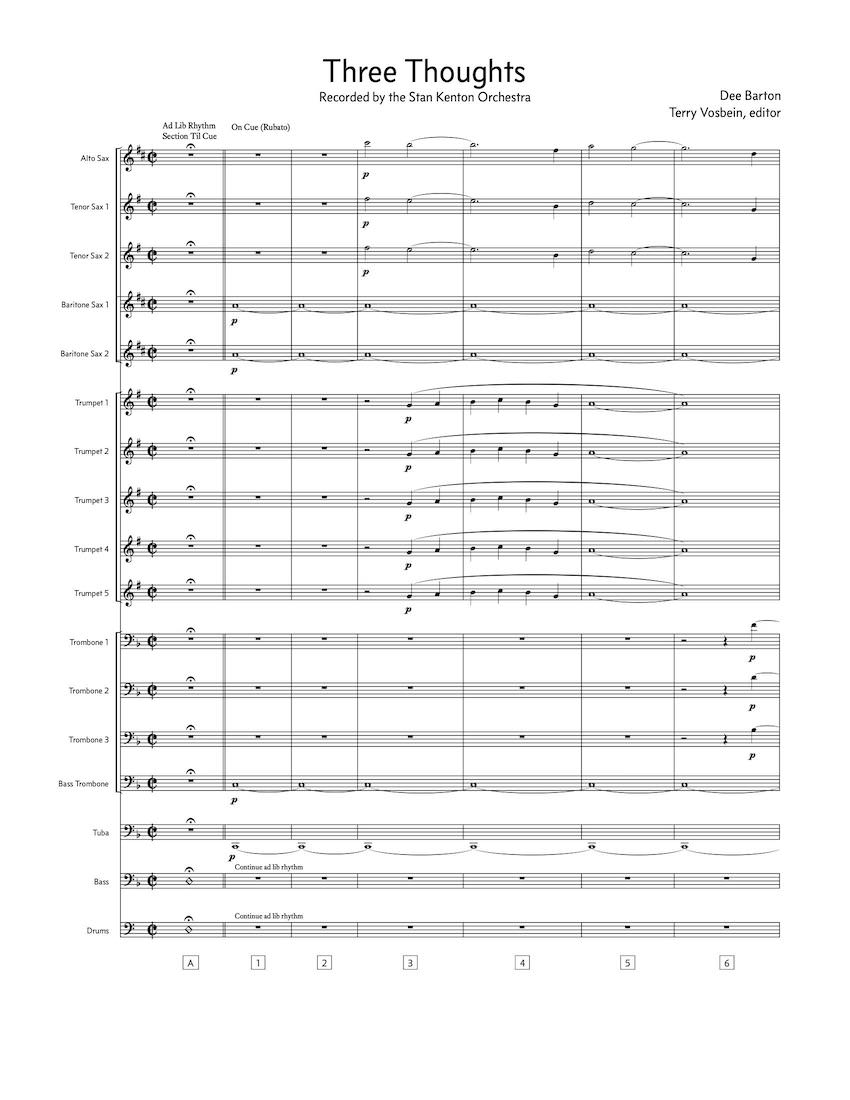

Three Thoughts

A New Day

Woman

Bonus tracks from live recordings

San Jose State College – August 1967

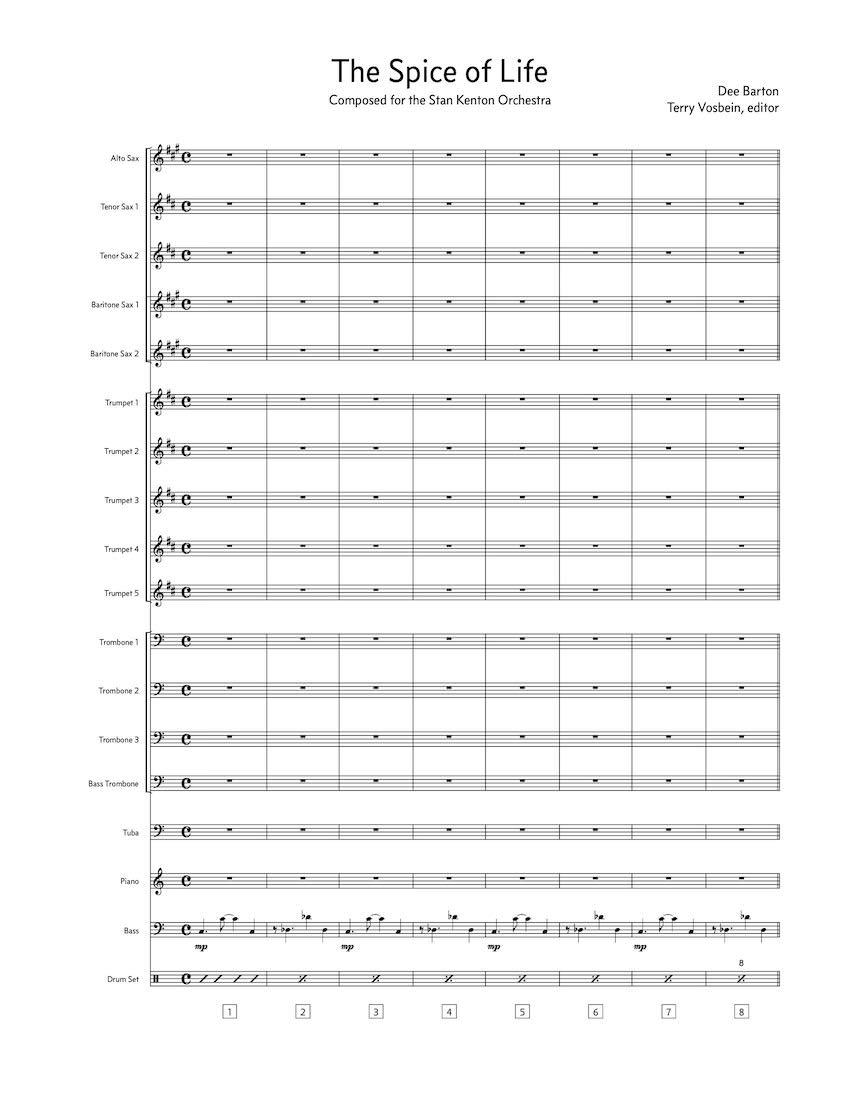

The Spice of Life

A New Day

Dilemma

Woman

The Singing Oyster

Here's That Rainy Day

Taboo

Lord Baltazar

Tune Up

Unknown #1

Unknown #2

- Personnel

Alto sax, flute

Ray Reed

Tenor sax

Kim Richmond

Mike Altschub

Bari sax

Mike Vaccaro

Bari & bass sax

Earle DumlerTrumpet

Mike Price

Jim Kartchner

Jay Daversa

Carl Leach

John Madrid

Trombone

Dick Shearer

Tom Whittaker

Tom Senff

Jim Amlotte (b-tb)

Tuba, b-tb

Graham EllisPiano

Stan Kenton

Bass

Don Bagley

Drums

Dee Barton

- Vosbein essay

The Stan Kenton Orchestra was always known as an arranger’s band. Some of the best of the business wrote for his band. But only a small handful of these artists were honored with an entire album of original compositions. Bob Graettinger and Johnny Richards each had two; Bill Holman, Bill Russo, Gene Roland, and Dee Barton each had one.

Barton was already composing exciting works as a college student at the North Texas State University when Kenton invited him to join his trombone section in 1961. He immediately waxed two of his originals and included them on the Grammy winning “Adventures in Jazz” album. Barton played trombone for a while before jumping to the drum chair, staying until the end of 1963. He returned four years later as drummer/composer, and the band started performing his music on a regular basis.

By the end of 1967 this music was finely honed and Kenton was ready to commit it to wax. Recorded in two 3-hour afternoon sessions on consecutive days in December 1967, the recording proved to be more efficient than most. Three songs one day, four the next. Two of them were finished with just one take. Something special had taken place.

The band was quite comfortable with this music. They had been performing these charts for many months by this point. Newly found recordings demonstrate the band performing these pieces (and a few other Barton titles) five months earlier at a summer music camp. And they are already executing them to near perfection.

Barton the drummer was the consummate propulsion unit for these charts. And the two featured soloists were ideal for the mission. Ray Reed’s exploratory solos on alto sax and flute are well-matched with Jay Daversa’s unending creativity. They are the only soloists on the album, yet it never gets tiresome. They understood what Barton was doing and were able to take his pieces to the next level.

As different as Barton’s writing is from the many other contributors to the Kenton band book, it is all Kenton. It has extremes of dynamics, tempos, and ranges. It is dramatic. It has probing solos. But it also sizzles, with a feeling of forward moving exploratory jazz.

This proved to be Kenton’s last purely jazz album. In many ways, it is perhaps his “jazziest” disc. No influences of Stravinsky or rock to be found. Just hard blowing exciting pure jazz.

Barton’s orchestrations are very clean. He rarely mixes sections, preferring the pure sounds of trumpets, trombones, and saxophones. In the many scale-based melodies, the instruments are generally in unison or octaves. Shout choruses, both loud and soft, are comprised almost entirely of chord tones, with few passing tones to be found. He occasionally uses quartal voicings in the more modal pieces, such as Man. Four of the seven tracks begin with slow brass chords before giving way to more upbeat tempos (Three Thoughts, Man, Woman, Dilemma). One is a lilting jazz waltz (The Singing Oyster). One is slow throughout (Lonely Boy).

There are generally two or three themes in each piece. A New Day and Woman are in a standard AABA layout; The Singing Oyster is AABBAA; Three Thoughts and Dilemma each contain three sections that Barton mixes up with no real pattern. Lonely Boy has a single 18 bar melody.

There is variety in Barton’s choice of meters. One is in 5/4, one mixes 5/4 and 3/4, two are in 3/4, and the remaining four are in 4/4. The tempos range from slow introductions to the fleet footed Dilemma, clocking in at 240 beats per minute.

Barton utilizes the Kenton band instrumentation of the late sixties, with five saxes (ATTBB), five trumpets, four trombones, tuba, bass, and drums. On Woman, Ray Reed plays flute. And on Lonely Boy, the second bari sax plays bass sax. Although Kenton can be heard comping on a few of these pieces in live recordings, he is heard on just one track on the LP (The Singing Oyster), with a small, yet important, role.

Although these seven titles were not conceived as a suite, they work beautifully as a jazz concerto for sax and trumpet, sharing timbres, drive, and a forward moving energy. This LP demonstrated that Kenton could play pure jazz, without the extravagancies of his more grandiose projects. This album makes a point.— Terry Vosbein

- Original album liner notes

This is not just another jazz album.

It is a tribute to the mutual respect one composer holds for another. For with this richly inventive collection of jazz standards, Dee Barton emphasizes that he, too, belongs in that select company of orchestrators who have helped make Stan Kenton’s name synonymous with contemporary music.

A member of the orchestra since 1961, Dee began his career with Stan as jazz trombonist. After the band’s return from Europe, two years later, he gave up his trombone for the drum chair. Obviously, as evidenced by the dynamic performance he gives on this album, a sound decision.

As far back as Dee can remember, he's always wanted to write for the Kenton Orchestra: “As a matter of fact, much of the material I wrote while attending North Texas State University was sketched with Stan's .band in mind. little did I realize that two things I composed in my senior year, Waltz of the Prophets and Turtle Talk, would be used a year later in a jazz album he recorded with the mellophoniums.”

Although Barton has taken an occasional leave of absence to front his own group and to compose jingles for advertising agencies (“…an experience that will stay with me for some time”); his first love Is writing for a big band.

“When you write for all the sections, you not only gain an abundance of freedom, but communicate a fresh point of view. I especially enjoy building a mood and then letting a soloist improvise over my harmonic and rhythmic structures. As long as he doesn't violate the order in which I've arranged them, I'm never too concerned with what he does.

“For me, this is contemporary writing in its most original form. Anyway, who's to say what's right and what’s wrong? I've always felt that the biggest contribution we could make to music would be to throw away the rule book. It's time we stopped trying to enforce personal prejudices on the 19 or 20 guys who are responsible for breathing life into our arrangements.

“Whenever possible, I think it important to establish a rapport between the musicians and music For by doing so, you’ll enrich, and make more meaningful, the listening experience.”

It is apparent, from first to last note, that this album was created by men who share Dee Barton’s musical philosophy. In a superb blend of musicianship and imaginative writing, Dee has forcefully etched for Stan Kenton's creative world a concert program of towering significance.

SIDE I

Man. (4:27) Like an amiable conversation among friends, Man bubbles with an effusive jazz spirit. After a sinewy Introduction, the trombones set the mood of things to come. Written in 3/4 time, this rollicking arrangement is complemented by solos from Jay Daversa and Ray Reed. Muscular ensemble work, kept on fire by Barton's drums, builds toward a spark-filled climax ringed with Mike Price's trumpet resolutions.

Lonely Boy. (2:48) Lush, lovely, and Latin, this blues standard was written early one morning as the band made t heir way across the desert into New Mexico. Notice the feeling of great longing as the sections drift back and forth over the 5/4 accents of the bass and drums. Particularly arresting is the way the saxes keep re-stating the classically sad melody line.

The Singing Oyster. (3:34) follows its title and jumps right into uptempo play. Spotlighting the muted trumpet of Daversa, this musical whimsy emphasizes the shoulder-shaking sound of the Kenton Orchestra.

Diiemma. (5:54) Opening with a stately declaration from the full orchestra, Dilemma demonstrates Barton’s ability to fuse scattered bursts of dissonance with orthodox harmonies. Solos by Daversa and Reed set the direction, with all sorts of happy sounds emerging from the sections. Paced by brisk rhythm figures, Dilemma builds to hurricane proportions, abundantly fulfilling Barton's desire to “communicate a fresh point of view.”

SIDE II

Three Thoughts. (5:30) is a musical mobile with which Barton blends colorful tonal sequences into explosions of excitement. The driving opening, frontlined by Don Bagley’s bass, creates a rich back drop for solos by Daversa and Reed. Countermelody builds upon countermelody as the sections race up and down Barton’s pyramiding harmonic structures. From beginning to end, Three Thoughts is a brilliant example of the beauty and power unleashed by Stan Kenton's Orchestra.

A New Day. (7:32) again showcases the lyrical trumpet of Jay Daversa. After a haunting, baroque statement from the brass, Daversa poignantly describes the highs and lows that evolve between dawn and dusk. His free-form soliloquy fills the air with bittersweet memories, challenging the listener with highly personal, yet universal statements about life and love.

Woman. (6:16) is a sensitive, witty composite of ladies known and loved. After a puckish introduction by Daversa and Ray Reed (this time on flute), subtle underscoring takes over until trumpet and flute go their separate ways. By establishing a "chatty" narrative that evokes both humor and affection, Barton creates a resonant portrait of a woman who is all things to all men. And who never misses an opportunity to tell you, “she, too, loves you madly.”— Noel Wedder

- Tidbits

Man is the most quartal of the batch, with melodies and harmonies both being derived from the perfect fourth. The opening fanfare announces the significance of the perfect fourth. First stated in octaves, the ascending fourths are then stated in five-part quartal harmony, before giving way to the fast jazz waltz. The melody is expressed in long notes, with interjections of fast runs from the unison alto and trumpet. The final four measures of dissonant sax chords were added in pencil by the players to their parts. They are comprised of five-part harmony, stacked this time in fifths.

Lonely Boy is the only Latin flavored composition on the album. A moderately slow 5/4 meter in G minor. It is the simplest in structure, a 16 bar melody is repeated four times. There are no solos, improvised or written. Six additional choruses are notated in the parts, containing ensemble passages, as well as an alto and tenor sax solo. These were omitted on the LP.

The Singing Oyster, originally titled “The Gay One,” dates to Barton’s NTSU time. It’s a lilting waltz, that combines flowing unison melodies and hard swinging shout choruses. After the melody is presented, and the two soloists have their say, there are 80 bars of full-ensemble, combining block-chords and unison lines, starting softly and building quickly. A sudden return to bar one brings the composition home.

Dilemma’s original title was “The Chez Rah.” Barton frequents the dominant 7th chord with a lowered fifth, giving a whole-tone sound to the mix. This is another chart with a slow block-chord intro that soon swings fast and hard.

Three Thoughts begins with a dirge-like full-band rubato chorale, suspended above the bass and drums flying along in an up-tempo swing. Once this intro is over, the most swinging piece on the LP really gets going. After a memorable unison trombone melody, the band screams a bit and sets off the trumpet and alto solos. There is a brilliant shout chorus after the alto solo that goes form pianissimo to fortissimo in four bars and back down again. The parts end at bar 192. But pencil marking indicate that the first 15 bars, the dirge like opening, are to be repeated.

A New Day features the solo trumpet almost throughout. After a ponderous introduction the first theme (AB) is stated by unison trumpets. Each successive chorus is AABA. After the solo trumpet states the theme, the band jumps into double time and a lengthy ad lib solo begins. A shout chorus follows pitting the block chord brass against unison saxes. The solo returns, supported by screaming full ensemble chords. This dissolves into a cadenza and a return to the original melody and feel.

Woman, whose original title was “The Muse,” is a feature for trumpet and flute, who often play the melody together. Like several others, this medium up-tempo tune begins with a slow series of chords in the bones, before turning into an up-tempo rhythmic romp. The bulk of the composition is made up of a bar of 5, two bars of 3. This repeats, followed by three bars of 5, and two to four bars in 3.

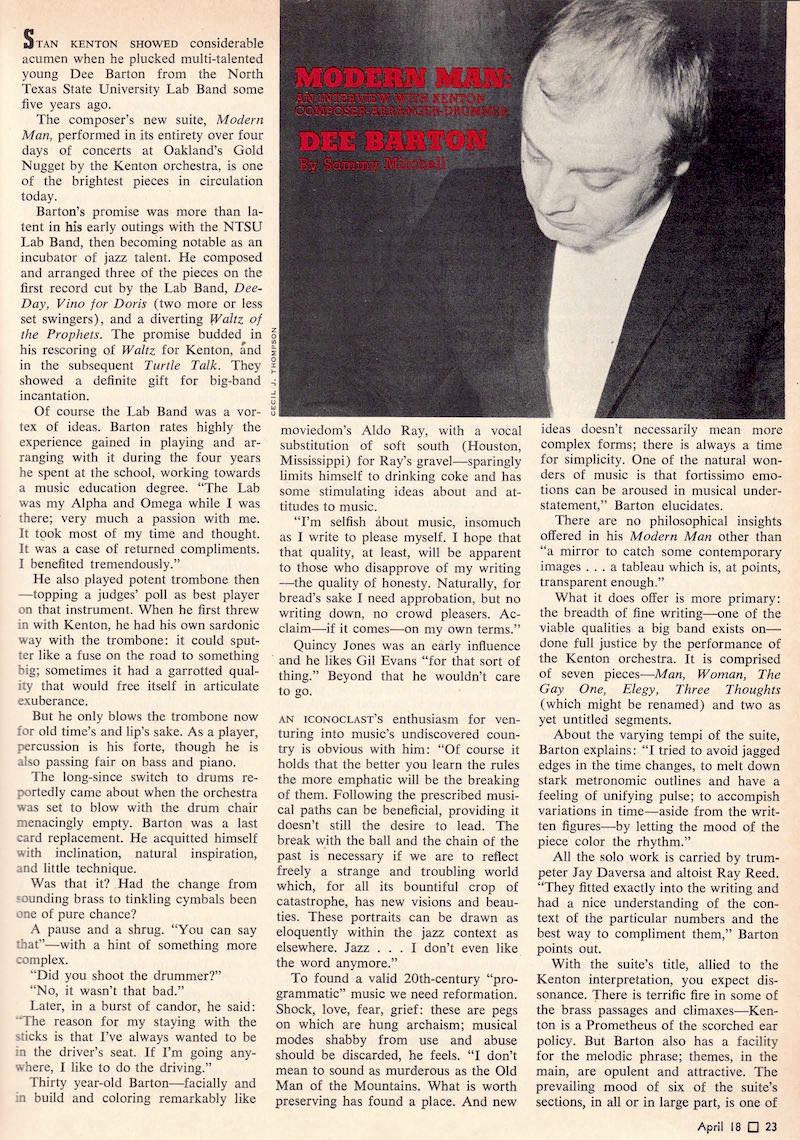

- Modern Man. An Interview with Kenton Composer-Arranger-Drummer Dee Barton

Mitchell, Sammy. “Modern Man. An Interview with Kenton Composer-Arranger-Drummer Dee Barton.” Down Beat 35, no. 8 (1968-04-18): 23–24.

Stan Kenton showed considerable acumen when he plucked multi-talented young Dee Barton from the North Texas State University Lab Band some five years ago.

The composer’s new suite, Modern Man, performed in its entirety over four days of concerts at Oakland’s Gold Nugget by the Kenton orchestra, is one of the brightest pieces in circulation today.

Barton’s promise was more than latent in his early outings with the NTSU Lab Band, then becoming notable as an incubator of jazz talent. He composed and arranged three of the pieces on the first record cut by the Lab Band, Dee Day, Vino for Doris (two more or less set swingers), and a diverting Waltz of the Prophets. The promise budded in his rescoring of Waltz for Kenton, and in the subsequent Turtle Talk. They showed a definite gift for big-band incantation.

Of course the Lab Band was a vortex of ideas. Barton rates highly the experience gained in playing and arranging with it during the four years he spent at the school, working towards a music education degree. “The Lab was my Alpha and Omega while I was there; very much a passion with me. It took most of my time and thought. It was a case of returned compliments. I benefited tremendously.”

He also played potent trombone then—topping a judges’ poll as best player on that instrument. When he first threw in with Kenton, he had his own sardonic way with the trombone: it could sputter like a fuse on the road to something big; sometimes it had a garrotted quality that would free itself in articulate exuberance.

But he only blows the trombone now for old time’s and lip’s sake. As a player, percussion is his forte, though he is also passing fair on bass and piano.

The long-since switch to drums reportedly came about when the orchestra was set to blow with the drum chair menacingly empty. Barton was a last card replacement. He acquitted himself with inclination, natural inspiration, and little technique.

Was that it? Had the change from sounding brass to tinkling cymbals been one of pure chance?

A pause and a shrug. “You can say that”—with a hint of something more complex.

“Did you shoot the drummer?”

“No, it wasn’t that bad.”

Later, in a burst of candor, he said: “The reason for my staying with the sticks is that I’ve always wanted to be in the driver’s seat. If I’m going anywhere, I like to do the driving.”

Thirty year-old Barton—facially and in build and coloring remarkably like moviedom’s Aldo Ray, with a vocal substitution of soft south (Houston, Mississippi) for Ray’s gravel—sparingly limits himself to drinking coke and has some stimulating ideas about and attitudes to music.

“I’m selfish about music, insomuch as I write to please myself. I hope that that quality, at least, will be apparent to those who disapprove of my writing—the quality of honesty. Naturally, for bread’s sake I need approbation, but no writing down, no crowd pleasers. Acclaim—if it comes—on my own terms.”

Quincy Jones was an early influence and he likes Gil Evans “for that sort of thing.” Beyond that he wouldn’t care to go.

An iconoclast’s enthusiasm for venturing into music’s undiscovered country is obvious with him: “Of course it holds that the better you learn the rules the more emphatic will be the breaking of them. Following the prescribed musical paths can be beneficial, providing it doesn’t still the desire to lead. The break with the ball and the chain of the past is necessary if we are to reflect freely a strange and troubling world which, for all its bountiful crop of catastrophe, has new visions and beauties. These portraits can be drawn as eloquently within the jazz context as elsewhere. Jazz…I don’t even like the word anymore.”

To found a valid 20th-century “programmatic” music we need reformation. Shock, love, fear, grief: these are pegs on which are hung archaism; musical modes shabby from use and abuse should be discarded, he feels. "I don’t mean to sound as murderous as the Old Man of the Mountains. What is worth preserving has found a place. And new ideas doesn’t necessarily mean more complex forms; there is always a time for simplicity. One of the natural wonders of music is that fortissimo emotions can be aroused in musical understatement,” Barton elucidates.

There are no philosophical insights offered in his Modern Man other than “a mirror to catch some contemporary images…a tableau which is, at points, transparent enough.”

What it does offer is more primary: the breadth of fine writing—one of the viable qualities a big band exists on—done full justice by the performance of the Kenton orchestra. It is comprised of seven pieces—Man, Woman, The Gay One, Elegy, Three Thoughts (which might be renamed) and two as yet untitled segments.

About the varying tempi of the suite. Barton explains: “I tried to avoid jagged edges in the time changes, to melt down stark metronomic outlines and have a feeling of unifying pulse; to accomplish variations in time—aside from the written figures—by letting the mood of the piece color the rhythm.”

All the solo work is carried by trumpeter Jay Daversa and altoist Ray Reed. “They fitted exactly into the writing and had a nice understanding of the context of the particular numbers and the best way to compliment them,” Barton points out.

With the suite’s title, allied lo the Kenton interpretation, you expect dissonance. There is terrific fire in some of the brass passages and climaxes—Kenton is a Prometheus of the scorched ear policy. But Barton also has a facility for the melodic phrase; themes, in the main, are opulent and attractive. The prevailing mood of six of the suite’s sections, in all or in large part, is one of bona fide swing. The seventh is a slow Latin.

Commencing with stentorian brass, the trombones playing with fine pomp, Man soon takes on palpitating form (“…though in three, it has a two feeling…then four, and into three again…”), evolving in a fast turbulence of brass and lissome sax figures. Daversa’s and Reed’s solos had a melancholy tinge, expressive and plaintive, in contrast to the piercing ensemble. The drive gradually ebbed into a long mournful chord with Reed still poignant, and there was the impression that the conclusion was on a wistful note, almost a whimper. But after a pause, the frenzy picked up again and Man went out on a sulphurous bang.

Woman, naturally, has some changes (“…seven bars of 5/4, two of 3/4, most of the rest in 11/4…”). She enters on a satirical mocking note, then is pleasantly transformed into an effervescent miss, with Reed on flute dueling the theme with Daversa. Reed pipes as eloquently on flute as on alto. He and Daversa—who played muted trumpet throughout—stayed in a light vein, sparkling against brass that increased in fervor, rising to hysterics. The saxes rippled and surged in a repetitious, resplendent passage that heightened the excitement. A diminuendo in drive brought on a lull—then Daversa and Reed ducted in carefree fashion to the finale.

Despite the title, there’s nothing coy about The Gay One. (“A little thing in three; straightforward.”) It has plenty of cavalier dash and bite. Saxes sportively set out its jaunty theme, countered by a manly thrust from the brass, banshee screeches launching Reed and Daversa on solos of high-flying aplomb that had appropriate sprightlincss. Slight, perhaps, but very listenable. A small gem in the jazz waltz genre.

Elegy isn’t all lamentation, though in the opening and closing sections the trombones and tuba predominate in dirge-like effects and the trumpets have a razored tenseness. Daversa’s trumpet moved in limpid and seraphic fashion, poised above pensive orchestration, then paced the ensemble as it metamorphosed by degrees into a full-blooded, frantic cry. There was a schizophrenic change to tranquility, then the fury of 4/4 gathered again, plangent brass at a boisterous speed that resolved into slow- moving ominous trombones with Daversa serene—after brilliant and sustained runs—over the last sinister chord.

Bass and drums blazed into an ardent attack in the opening measures of Three Thoughts, unflagging through several bars with the orchestra silent. Its mood—after a fanfare—was of a funereal flavor, moving slowly, impervious to the fast rhythm. (“Thoughts is an energy piece…the pulse there, but constantly changing…the rhythm with completely different accents to the band, not related; at other points building with it.”) The vigor of the rhythm gradually abated, dissolving in the orchestra’s restrained tenor. Gloom lifted, and the mood became lambent. The pulse quickened into feverishness, the orchestra moving with it, the brass and saxes with a full spread of sails. Reed and Daversa had to blow hard and agile to avoid the crushing weight of the brass which came on like a juggernaut. Dissonant roars finally quieted to a calm close.

Of the two untitled pieces, one is a Latin in 5/4, short, with snatches of alto and muted trumpet. The trumpet section on percussion swelled the rhythm briefly; Steve Genardini’s conga colored in most of the Latin timbre. Bass sax and baritone played low, giving the reeds a gruff edge, almost a grunt. The brass flared fitfully. It was on the pensive side, with a quality of slow chant; very different from Kenton’s usual conquistador approach to the other America.

The last (“…an energy piece…a hard core of 4/4”) erupts out of the same volcano as Man, Elegy, and Thoughts, and like them has surprising twists and subtleties. Daversa and Reed duet the slow introductory theme, blandly controlled against gentle orchestral undulations transformed into dissonant tremors. During a long solo, Daversa started high on several runs, playing beautiful descending phrases. The brass was at its most omnipotent; wall-shaking Jerichoean blasts from the trumpets and the trombones at a height of harsh power; the saxes weaved through the clamour lucidly with plenty of limber and spirit. Reed, on his solo, had to wail like a muezzin, rising articulate above the abandon. Daversa joined him and they went into a wild jamming, alternating between atonal and melodic passages. This piece too had moments of serenity, but shortlived. It was up and away, and a banners streaming exit.

The personnel at the Oakland concerts was the same—Mike Price, Carl Leach, Jim Garchncr, John Madrid, Daversa, trumpets; Dick Shearer, Tom Whittaker, Tom Scnff, Jim Amlotte, Graham Ellis (doubling tuba), trombones; Reed, Mike Altchue, Bob Dall, Mike Vaccaro, Darrel Dumler, reeds; Kenton, piano; Jerry Johnston, bass; Barton, drums; Steve Genardini, conga—that recently cut the suite for Capitol records. The band’s form is extraordinarily good, with what must be the freshest set of faces Kenton has ever led into battle. A fountain of youth which Kenton fronted like Ponce de Leon.

In numbers apart from Barton’s compositions, young tenorist Mike Altchue—shades of Coltrane occasionally hovering—showed flair. Shearer on trombone is always an asset and bass trombonist Amlotte, though never spot-lighted, is beautifully felt. On lead, Mike Price honed the trumpets to a razor sharpness. Genardini’s conga was seldom silent; he was used effectively on ballads and strong numbers.

Of course the standouts were Reed and Daversa. Strongly individual in their playing, they yet changed like chameleons to blend with the varied writing and colors of Barton. The show-casing of them in Modern Man may have been incidental—but a showcase it is.

As keepers of the pulse, Barton, Johnston, and Genardini were an ideal leaven, smooth on the low speeds and raising the orchestra to a smoky ferment on up tempos. Barton’s drumming is powerful and ebullient; he likes to sink the spurs deep, staying well on top of the band when it stretches out.

It played its last date after the Oakland concerts. Kenton hopes to reform it, intact, this June. He was enthusiastic about Barton’s future. “I’ve watched the maturing of his talent through the years. He’s coming up with some heady brews.”

He takes a hand in Kenton’s arranging. Here’s That Rainy Day and his own composition Love Is Such A Simple Thing (Kenton, announcing, said he thought it was a hassle) is couched in the band’s amiable ballad style. The nucleus of a dozen or so compositions has been formed; this coming period away from the road should help develop them.

One of the “brews” Kenton spoke of might be The Beauty of Silence, premiered at the first of the recent Neophonic concerts.

Barton’s description: “Its duration is about 15 minutes; a series of parts, some fragmentary, interposed by periods of silence that are occasionally quite ex- tensive…from 10 to 12 seconds. A sombre mood is built…will dwindle and stop. Or a furious passage…the silences arc a natural extension of the previous musical mood, not breathing spaces. Times for thought and assimilation.”

From the height he once occupied, Kenton has had a Luciferian fall; a descent from grace in some quarters, though to a following too large to be called a cult he still lords it in the big-band realm. Barton, in his bold writing, might do much to lift Kenton from relative limbo.

- Down Beat record review

Harvey Siders. "Record Review. Stan Kenton Conducts the Jazz Compositions of Dee Barton." Down Beat. 1 May 1969. 22.

STAN KENTON CONDUCTS THE JAZZ COMPOSITIONS OF DEE BARTON—Capitol 2932: Man; Lonely Boy; The Singing Oyster; Dilemma; Three Thoughts; A New Day; Woman.

Personnel: Mike Price, Jim Karthner, Carl Leach, John Madrid, Jay Daversa, trumpets; Dick Shearer, Tom Whittaker. Tom Senff, Jim Amlotte, trombone; Graham Ellis, tuba; Ray Reed, Mike Altschul, Kim Richmond. Mike Vaccaro, Earle Dumler. reeds; Kenton, piano; Don Bagley, bass; Barton, drums.

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ½

The first thing that impresses one in this album is the playing of Dee Barton, despite the fact that his writing is what’s being touted. Although Barton began his career as a trombonist, he is so thoroughly a drummer now that his charts reflect his percussive thinking. He instinctively and pulsatingly leaves the gaps that can only be filled by drum flurries, or else his melodic lines are such that they lend themselves to rhythmic doubling.

It's most effective, but in the process, he has injected the current Kenton bag with a somewhat foreign flavor. Frankly, it doesn't sound like a Kenton aggregation; it approximates Rich or Bellson—muscular groups pushed from behind rather than led from out front.

But that’s not criticism—merely comment. Within this atypical framework, there are exciting pages of ensemble togetherness, moments of free-form flirtation, a good cross-section of orchestral moods, and above all, showcases for the band’s outstanding soloists: trumpeter Jay Daversa and reedman Ray Reed.

Too bad that no other soloists were heard from. Daversa enhances every track; Reed is heard on all but two. As remarkable as they are, it’s a bit unfair. The only other strands of sound that can be separated for purposes of crediting are Bagley’s authoritative bass lines and Mike Price’s fine screech work on Man.

The tracks that how Barton’s writing skill at its best are Three Thoughts and Woman. Thoughts range from a dignified opening statement to some driving pedal points that provide excellent foundation for Daversa and Reed, and tight, concerted voicings, reprised by broad polyphonic statements. Woman shows a swinging playfulness, muted trumpet and flute engaging in a tricky dialog. A New Day has the old Kenton trademark of rich trombone clusters, plus hauntingly beautiful solo statements by Daversa. Dilemma has the toughest orchestral fabric. Its momentum is assured by Reed’s frenetic solo and his and Daversa’s free sorties within some well-controlled orchestral comping.—Siders

- Jazz Monthly record review

Priestley, Brian. "Record Review: The Jazz Compositions of Dee Barton." Jazz Monthly, October 1969: 19.

STAN KENTON CONDUCTS THE JAZZ COMPOSITIONS OF DEE BARTON

Capitol ST 2932 (37/5d.)

AS WE ALL know from painful experience, a reviewer who is the victim of his prejudices is worse than useless, and so I have made strenuous efforts to approach this as a showcase for Dee Barton (on a par with the recent Dankworth-sponsors-Ken-Wheeler LP). If I had been successful in ignoring the presence of Kenton, whose playing contribution is negligible, I would have said that this relatively unknown composer (Waltz of the prophets etc) has a good grasp of standard arranging techniques and varies his moods nicely, but that it all seems a bit soulless. Despite one or two original ideas, he doesn’t exactly have a flair for melody, and neither do the two soloists Daversa and Redd; what bite there is comes from the brass but, since Barton has tried to do more than just pander to the ensemble, the whole things falls a bit flat. There is no such thing as a typical Kenton record and, although it suffers from some of the faults of the genre, this one has a few saving graces. On the other hand, Ken Wheeler has a touch of genius, and what Dee Barton was aiming at is achieved on “Windmill Tilter” (Fontana STL5494).BRIAN PRIESTLY

- Blindfold Tests

Don Ellis – Dilemma

Could you play the beginning of that again, please?…

That was a very curious mixture indeed of I 950 style big band writing, combined with some avant-garde solos by the trumpet and alto. I have no idea who….

I have only heard Jimmy Owens once, one solo he played in Berlin with Dizzy’s orchestra, but this sounded like it could possibly be him. I haven't heard the band, but I understand that Duke Pearson has a band that has been recording in New York; perhaps this is his band. This is just a wild guess.

It was interesting; I kept wondering if the two style s were ever going to get together, and they never did. But it was an interesting juxtaposition in any case. This particular kind of big band writing, in recent months I've pulled out everything in my book that even remotely resembles it, because it just seems to be so out of tune with what's happening today.

When people think of big-band writing, outside of say Duke, Basie or Kenton, this is what you usually come up with. It just sounds too dated for my personal taste, although it was very well written and if this had been recorded 10 years ago, it would have been fantastic, but today being what it is, it doesn't really get to me.

The trumpet player had some nice ideas. There again, I didn't hear any big overall, linking motifs or anything within the solos that held them together—just sort of snatches of nice little ideas here and there. All I can basically say is that it was rather curious and it was obviously well played on everybody's part, so for musicianship we have to give it a good rating, around four stars. But for my own personal enjoyment it would be more like three.

Frank Strozier – Lonely Boy

Well, I don’t know who any of the players were. The band sounded good and I thought it was a good orchestration. It was very interesting, very enjoyable to listen to…

I think that for what it was, it got the message across to me. Four stars.

Tommy Vig – Man

It's Stan Kenton's band. It was a mod al composition and arrangement with different superimposed feelings on the 3/4 time. Like the usual big band sessions, they probably didn't have enough time to correct other little mistakes, or they just didn't want to edit it too much…the lead trumpet player certainly plays very high. The soloists were mostly, to use one of your expressions, perfunctory. However, it was pure jazz with no other but musical purposes, and as we have seen, that in itself is a rare quality. So, for the braveness…I don't know when it was recorded. If it was recorded recently, certainly it's a great merit that it's free and trying to say whatever he wants to say, regardless of commercial purposes. For that I would give 3½ stars. Judging it from the highest possible viewpoint of pure jazz, 2½.

- Arrangements & compositions by Barton created for Kenton

* indicates original composition

Bondafelina

“Bound to Be Heard” incidental music *

The Charge of Attila *

Didn’t We? (1970)

Dilemma (The Chez Rah) * (1967)

Easy *

Ecnarelc Tf 11 *

Flower Child *

Glass *

Here’s That Rainy Day (1967)

How Are Things in Glocca Morra? (1968)

Lady Bird

Lonely Boy * (1967)

Lord Baltazar *

Love Is Such a Simple Thing *

Lullaby from “Rosemary’s Baby” (1968)

MacArthur Park (1968)

Man * (1967)

Move I *

Move II *My Foolish Heart (1968)

A New Day (Elegy) * (1967)

Passion Suite * (1968)

Peace *

Personal Sounds - Parts 1-9 * (1968)

Picnic Waltz

Prologue *

Sassie *

The Singing Oyster (The Gay One) * (1967)

The Snake * (1968)

The Spice of Life *

Suite *

Sunday's Smiling Girl *

Swing Machine *

Tharus *

Three Thoughts * (1967)

Tune Up

Turtle Talk * (1961)

Waltz of the Prophets * (1961)

Woman (The Muse) * (1967)

Jay Daversa and Terry Vosbein

New Orleans, 2024

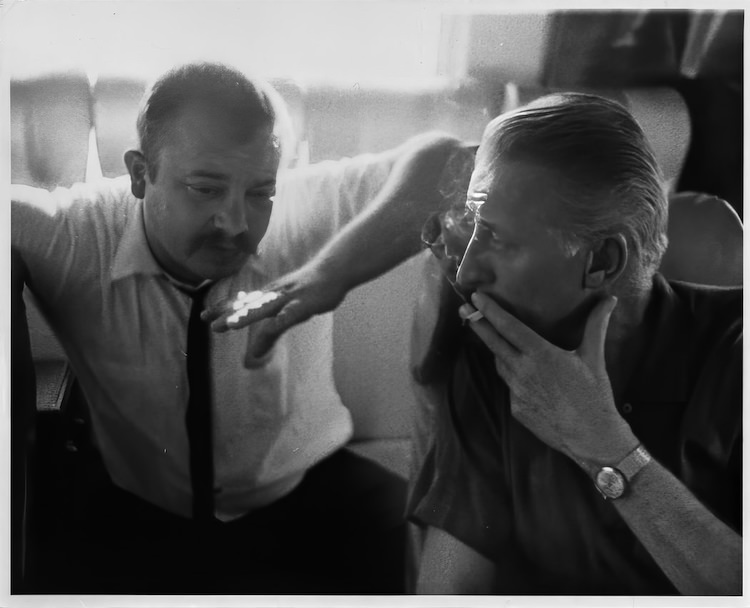

Photograph of Stan Kenton and Dee Barton

University of North Texas Libraries, UNT Digital Library

Stan Kenton Research Center

13 W Beverley Street

Staunton Virginia 24401

USA

© 2024